Touch and the Stress Response System

By Ruth Werner

https://www.massagetherapy.com/articles/jangled-adults

Soothing touch, whether it be applied to a ruffled cat, a crying infant, or a frightened child, has a universally recognized power to ameliorate the signs of distress. How can it be that we overlook its usefulness on the jangled adult as well?

What is it that leads us to assume that the stressed child merely needs “comforting,” while the stressed adult needs “medicine”?

— from Job’s Body: A Handbook for Bodywork by Deane Juhan

From the first day of school, massage therapists are taught that bodywork improves the function of many systems. We learn about its influence on muscle tone, circulation, lymph flow, and fascial mobility. We get less education about how massage influences hormones. That topic seems foreign and abstract, and it has to do with (oh no!) chemistry, so it’s easy to gloss over it and move on to more interesting (and more palpable) anatomy topics.

This is unfortunate, because the link between positive touch and healthy endocrine function is well-established, especially for infants and young children. The potential for positive touch to influence endocrine health among adults, however, is largely unexplored, and may well turn out to be one of the most profound benefits massage has to offer.

Let’s review some basic concepts about the link between the endocrine system and the sympathetic nervous system. We will see how touch deprivation leads to serious problems in hormone regulation, and in turn, overall health. And we will ask how touch can help to reestablish a healthy connection between autonomic and endocrine function.

The HPA Axis and the Stress Response System

The HPA axis refers to the connections that exist between three key structures: the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands. The neurological and chemical links between these structures determine our ability to adapt to, and adequately meet, the challenges that arise in our lives. At its essence, the HPA axis and the stress response system translate emotional state into physical response.

The hypothalamus, located deep in the brain, is a key player in many homeostatic functions. It also controls much of the endocrine system through its influence on the pituitary gland. While the pituitary is often called the “master gland,” the hypothalamus controls pituitary secretions through corticotropic releasing hormone (CRH) and through direct motor impulses.

The adrenal glands are likewise connected to the HPA axis through neurological and chemical means: Motor neurons extend directly from the brain to the adrenals for immediate response, and that response is reinforced by the release (from the pituitary) of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). (See the flow chart on page 126 for a map of these connections.)

Two adrenal secretions are at the center of the stress response: adrenaline (from the adrenal medulla) for short-term, in-your-face, we’re-all-gonna-die-now stress, and cortisol (from the adrenal cortex) for long-term, low-grade, grit-your-teeth, here-it-comes stress.

When the HPA axis is healthy, we release stress hormones in accordance with the threats we perceive — lots of hormones for big threats and just a little for smaller threats. Then, we burn through these chemicals quickly for a fast recovery. But when the HPA axis is inefficient, we secrete lots of stress hormones for big stressors, and we secrete lots of stress hormones for little stressors. The hormones linger in our bodies, so recovery is slower. Adrenaline and cortisol, which function best in small doses, cause extensive damage when they are present for prolonged periods.

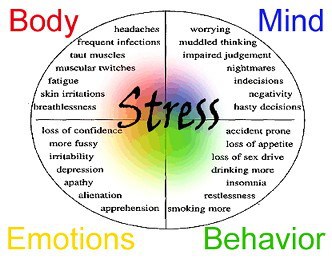

What Does Stress Do To Us?

For our hunter-gatherer ancestors, short-term stress occurred in the context of hunting or fighting. Adrenaline raises heart rate, increases blood pressure, and tells the liver to release sugar, all in preparation for dealing with a dangerous situation (the “fight or flight” reaction). Long-term stress for our ancestors was the threat of not having enough to eat. Consequently, our physiological response to long-lasting stress is to prepare for famine. We secrete cortisol, a glucocorticoid, to shift metabolism to the burning of proteins, including connective tissue, fascia, and muscle tissue. For people anticipating starvation, this makes sense: When the availability of food is in question, we become capable of literally “digesting” ourselves.

However, we no longer live the lives of our ancestors. Our experience of short-term, high-grade stress (outside of military conflict or fleeing from a hurricane) is probably something like a near miss on the highway. A deer darts out in front of us; we dodge it, but our heart pounds hard, our blood glucose goes through the roof, our saliva gets thick and sticky, our digestive tract shuts down, and our muscles get tight. The problem is, we’re still on the highway. We can’t get out of the car to use up all that adrenaline in the act of running away or fighting back.

Likewise, our experience of long-term, low-grade stress these days is probably not about whether we’ll have enough to eat this winter. It is more likely to be an abstract issue, like whether we bounced a check, our upcoming job interview, or our kids’ grades at school. But our bodies don’t know the difference between a physical threat like famine, and an abstract one, like an unexpected computer crash. As a result, a lot of people are walking around drowning in short-term and long-term stress-related hormones.

How does this affect health? Consider that adrenaline causes blood pressure to rise. This puts increasing strain on the lining of the arteries, which opens the door to atherosclerosis, heart attack, heart failure, and stroke. In combination, these illnesses account for nearly 40 percent of all deaths in the United States each year. Stress routes blood away from the digestive tract, leading to damage of the mucus lining of the stomach and an increased risk of peptic ulcers. Adrenaline causes the liver to dump sugar into the bloodstream; high blood glucose damages blood vessels, and it forces the pancreas to secrete extra insulin — paving the way for type 2 diabetes.

Low-grade stress has its problems as well. Cortisol dissolves connective tissue and suppresses inflammation. (This is why cortisone, a synthetic version of cortisol, is sometimes used to melt old scar tissue or reduce local inflammation.) When we secrete a lot of cortisol, we increase the risk of musculoskeletal injury. Cortisol is also associated with poor immune system function; during long-term stress, we become more vulnerable to infection. Abnormal cortisol levels and a sluggish stress response system are implicated in many common chronic diseases: Chronic fatigue syndrome, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, fibromyalgia, depression, and many other “stress-related diseases” list high cortisol and poor recovery from stress as leading factors.

Touch and Stress Management

Human beings and other animals are hardwired to be watchful for threatening situations. A part of our subconscious brain is always asking and answering the question, “Am I safe?” This is appropriate and healthy, as long as we are able to recover from stress as readily as we respond to it. Unfortunately, for many people, that is not an easy task. And it turns out that one of the most important variables in stress management is something over which we have no control: how much we were touched as infants and young children.

Studies conducted with various mammals reveal that key developmental processes are delayed or interrupted altogether when infant animals are deprived of maternal nurturing. Stress-related hormones are secreted in abundance, animals show poorer tolerance for challenging situations, immune systems are weaker, healing is slower, violent reactions are more frequent, and brain development, especially in the limbic system (the part of the brain that connects memory to emotion), is impaired. While it is obviously impossible to conduct similar studies on human babies, the tragedy of neglected infants is not hard to document. The children who survived Romanian orphanages to find homes in the United States and Canada are excellent examples of people who were touch-deprived in infancy. Many of these individuals have had long-term problems with memory and learning skills, some of them have never successfully developed emotional relationships with others, and their cortisol remains consistently high — all this accompanies the absence of nurturing, dependable touch during that pivotal formative stage of life.

Studies conducted with various mammals reveal that key developmental processes are delayed or interrupted altogether when infant animals are deprived of maternal nurturing. Stress-related hormones are secreted in abundance, animals show poorer tolerance for challenging situations, immune systems are weaker, healing is slower, violent reactions are more frequent, and brain development, especially in the limbic system (the part of the brain that connects memory to emotion), is impaired. While it is obviously impossible to conduct similar studies on human babies, the tragedy of neglected infants is not hard to document. The children who survived Romanian orphanages to find homes in the United States and Canada are excellent examples of people who were touch-deprived in infancy. Many of these individuals have had long-term problems with memory and learning skills, some of them have never successfully developed emotional relationships with others, and their cortisol remains consistently high — all this accompanies the absence of nurturing, dependable touch during that pivotal formative stage of life.

The need for abundant, nurturing touch in early life is well-established. The effects of touch deprivation in adults are not as understood. However, one population reveals some important clues: Elderly adults who live in isolation without a partner or a community get sicker, make more visits to the doctor or hospital, and die younger than their counterparts. It is reasonable to suggest that the need for touch doesn’t stop when we exit childhood, but the effects of touch deprivation among adults can be passed over or categorized as other problems including “stress-related diseases.”

Can Massage Make a Difference?

All evidence points to the importance of touch for adults as well as children. In our culture, this commodity is often in short supply. Our only appropriate contexts for nonsexual touch (outside of parent-child relationships) is in sports, greetings, healthcare, and professional grooming.

What do adults do, then, if we need to be comforted? We often don’t even identify the need as such. We misinterpret it as sexual desire, hunger, restlessness, or frustration. We might seek out sexual connections less out of love than out of need for contact. Or, in the absence of someone to hug our outer skin, we hug our inner skin by overeating. We try to satisfy our need for touch in many ways; some are more successful than others. Is it any wonder that massage therapy — educated, safe, professional touch — has found such a successful niche in American culture?

To the best of my knowledge (and I am perfectly happy to be proved wrong here), no formal research has yet been conducted specifically to explore the impact of massage on the stress response system. However, most massage therapists and their clients can attest that receiving massage is an important factor in reestablishing mental and emotional equilibrium. With the understanding that emotional state is translated into physical reality through the stress response system, it is clear that when we lower cortisol and adrenaline, we do more than improve mood. We also have influence on blood glucose, cardiovascular health, and immune system function. We learn about the health benefits of bodywork from the first day of massage school. Wouldn’t it be amazing if it turned out that many of these benefits are translated through the HPA axis and the endocrine system?

Ruth Werner is a writer and educator for massage therapists. She teaches several courses at the Myotherapy College of Utah and is approved by the NCTMB as a provider of continuing education. She wrote A Massage Therapist’s Guide to Pathology (Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins), now in its 3rd edition, which is used in massage schools all over the world. Werner is available at www.ruthwerner.com or wernerworkshops@ruthwerner.com.

I would like to thank Ruth for kindly allowing us to share this article with you all. I certainly thought it was very interesting hope you do also.

Penny Ellis

Founder/Director

www.balibisa.com

info@balibisa.com